Based on Plata, Fernández de Bobadilla & Tena (2025) – Biological Reviews

In the forests, orchards and parks we see every day, there is a network of interactions far more complex than we usually imagine. Among the branches of a tree, along the stems of crops or in urban gardens, a silent war is being waged: an evolutionary battle between ants, plant-feeding insects and tiny parasitoid wasps.

The scientific article on which this post is based — an extensive review published in Biological Reviews by researchers Ángel Plata, Maite Fernández de Bobadilla and Alejandro Tena — analyzes millions of years of shared evolution among three key groups of organisms:

- Phloem-feeding hemipterans, such as aphids, scale insects, whiteflies and mealybugs.

- Ants, which feed on the honeydew produced by these insects.

- Parasitoid wasps, natural enemies essential for keeping these herbivores under control.

Understanding these relationships is not merely a naturalist curiosity — it has direct implications for agriculture, biological pest control and conservation.

A powerful mutualism: Ants and hemipterans

Hemipterans that feed on plant phloem ingest a liquid extremely rich in sugars but low in nutrients. To compensate, they expel the excess as honeydew, a sweet and abundant syrup. This resource is pure gold for many ants, which have evolved to collect it, transport it and share it within the colony through trophallaxis.

In exchange for this constant energy supply, ants protect hemipterans from their enemies. As the authors note, this “food-for-protection” exchange forms one of the most widespread and successful mutualisms on Earth.

Ants:

- chase away predators,

- clean the bodies of hemipterans,

- move them to locations with better access to sap,

- and remove fungi or debris that could obstruct honeydew flow.

For hemipterans, the presence of ants can mean the difference between survival and collapse under pressure from natural enemies.

The enemy in the shadows: Parasitoid wasps

On the opposite side of this story are the parasitoid wasps, especially the tiny species belonging to the order Hymenoptera.

These wasps are essential to natural pest regulation: they search for hemipterans, lay an egg inside them, and the larva develops by feeding on the insect until it kills it. They are, in essence, highly specialized surgeons of biological control.

But their success is limited by a formidable obstacle: protective ants.

When a wasp attempts to approach an aphid or scale insect tended by ants, it is detected quickly. Ants may:

- bite it,

- chase it,

- force it off the plant,

- or even capture it and carry it into the nest.

This pressure is so intense that, according to the review, the presence of ants significantly reduces the ability of parasitoid wasps to regulate hemipteran populations.

How it all began: A 300-million-year evolutionary story

The article traces the origin of this complex relationship:

- Hemipterans emerged around 330 million years ago and developed specialized mouthparts to access phloem.

- Specialized parasitoids appeared during the Triassic, more than 200 million years ago.

- Ants, as we know them today, arose around 160 million years ago, but it wasn’t until the diversification of angiosperms that they began colonizing tree canopies and consuming honeydew.

From that moment, ants and hemipterans started co-evolving, forming increasingly tight mutualistic relationships. This had direct consequences for the evolution of parasitoids, which were forced to develop new strategies to face these powerful guardians.

The ants’ arsenal: Organized and efficient defense

The paper describes in surgical detail how ants defend their “herds of aphids”:

1. Direct attacks on adult parasitoids

Ants recognize wasps through:

- chemical signals (cuticular hydrocarbons),

- mechanical cues,

- or even behavioral changes in hemipterans when attacked.

Once detected, the wasp is antennated, bitten and chased. Some ant species can completely capture wasps and carry them into the nest to eliminate them.

2. Attacks on immature parasitoids

Even when a wasp successfully lays an egg inside a hemipteran, ants can detect subtle differences in scent and kill the parasitized individual, destroying the parasitoid inside.

3. Indirect mechanisms

The mere presence of ants creates an “ecology of fear”. Many parasitoids reduce:

- the time spent searching,

- their oviposition attempts,

- their reproductive activity.

It is an insect equivalent of the effect wolves have on deer in terrestrial ecosystems.

The wasps’ counterstrategies: A catalogue of evolutionary ingenuity

The review also explores the other side of this arms race: the surprising adaptations of parasitoids to evade ants.

1. Specialized behavior

Some wasps:

- move faster,

- oviposit in seconds,

- jump or fly erratically,

- or learn to avoid zones with high ant density.

There are even cases of behavioral mimicry, where the wasp imitates the way an ant walks to go unnoticed.

2. Chemical strategies

Perhaps the most fascinating:

- Chemical mimicry: some wasps copy the smell of aphids to camouflage themselves.

- Ant-larva mimicry: others acquire the odor of the colony and are treated as if they were brood.

- Repellent secretions: certain parasitoids release compounds that deter ants, such as actinidine.

3. Morphological adaptations

In some groups:

- bodies are harder,

- the abdomen is telescoped to oviposit from protected positions,

- and there are cases of ant-like morphologies, where parasitoids resemble small ants.

Not all ants or hemipterans are the same

One of the most important conclusions of the review is that the strength of this interaction varies enormously depending on context:

- Some hemipterans attract far more ants due to the quality of their honeydew.

- Certain ants (e.g., Lasius niger or Oecophylla smaragdina) are extremely aggressive; others far less so.

- Colony size, host plant, time of year and even the presence of competing hemipterans all influence the relationship.

The review also shows a clear research bias toward temperate ecosystems and aphids, while tropical groups such as mealybugs or whiteflies are much less studied.

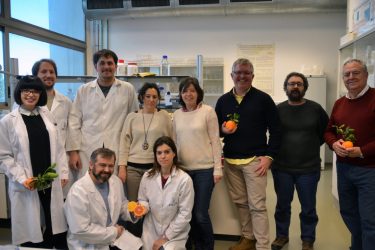

Implications for agriculture and biological control

Why does all this matter?

Because many hemipterans that depend on ants are major crop pests:

- citrus,

- fruit trees,

- tropical crops,

- horticultural systems.

When ants protect hemipterans, they greatly hinder the biological control performed by parasitoids. This means:

- pest populations can grow larger,

- damage increases,

- and alternative control methods become necessary.

The authors suggest that better understanding these interactions will allow us to:

- design strategies to reduce ant presence in crops using physical barriers or baits,

- select parasitoids adapted to ant-tended hemipterans,

- and better understand how environmental changes affect ecological balance.

An exciting future for research

The article concludes by highlighting several research directions:

- Explore more tropical ant species, which are understudied.

- Analyze how climate change may alter these interactions.

- Apply new technologies to study complex chemical signals.

- Improve ecologically-based agricultural strategies.

Ultimately, understanding these relationships not only improves pest control but broadens our perspective on how biodiversity persists thanks — or despite — millions of years of evolutionary tension.

Conclusion

The relationship between ants, hemipterans and parasitoid wasps is a fascinating example of coevolution, competition and cooperation that has shaped entire ecosystems.

Honeydew acts as the energetic engine behind mutualism; ants as tireless protectors; and parasitoid wasps as essential regulators of insect populations that damage our plants.

This evolutionary dance continues today, silent but crucial, among the branches of every tree and across every field. Understanding it is key for science, agriculture and the future of sustainable pest management.